Twas it?

The ever-deepening mystery at the center of Christmas's greatest text.

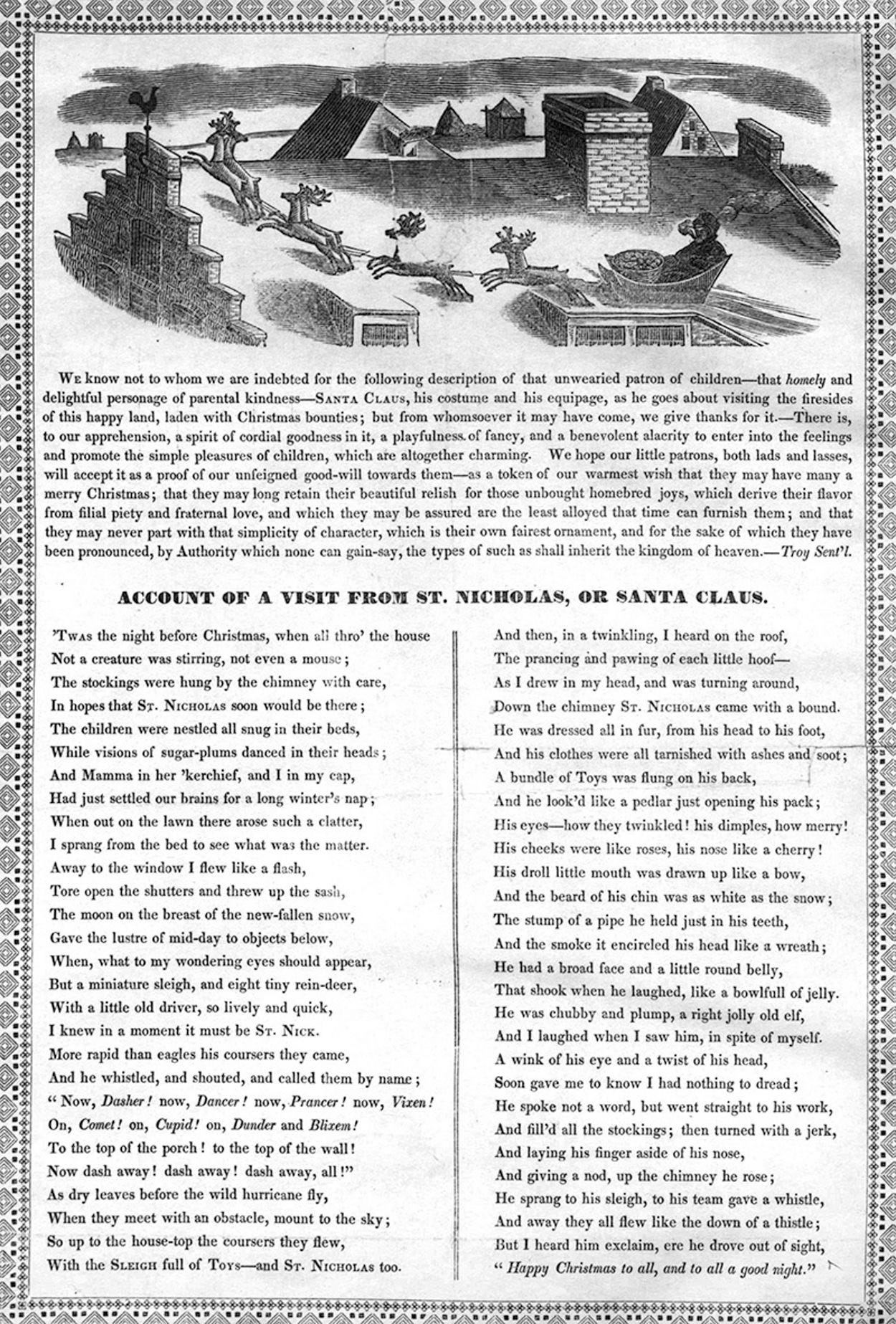

Every Christmas eve, my family gathers to read ‘A Visit From St. Nicholas,’ more popularly known by its first line: Twas the Night Before Christmas. This poem, written in 1822, published anonymously in 1823, is broadly credited with launching the modern American Christmas celebration, with its emphasis on children (vs. earlier versions focused on the working class) and Santa Claus, himself a recent creation.

We hand the slim volume around, each reading a page. Then, after ‘Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night,’ we close the book, and set it face up on the table where all can see its cover and byline: ‘A Visit From St. Nicholas by Clement C. Moore.’

Moore, the story goes, wrote the poem to read to his children one Christmas. Then, a visitor to his house had copied it down and brought it with her to Troy, New York, at which point it found its way to the local newspaper. It spread from there. Until, in 1837, Moore finally claimed authorship of the now famous poem. A happy Christmas was had by all.

Except for the descendants of Henry Livingston Jr.

The Livingston family was among the most eminent families in the United States. Their descendants and relatives by marriage include George H. W. Bush (as well, of course, as George W. and Jeb) , a congressman, a mayor of New York, and Eleanor Roosevelt. They had a big hand in the creation of the republic, and now, they claimed, in the creation of the modern Christmas.

Some time after Moore’s authorship became widely accepted, the Livingston family began to assert that their ancestor Henry Livingston Jr. — a gentleman farmer and poet — had actually written the poem. And Moore had stolen it. This in spite of the fact that Henry had never claimed authorship and the dates didn’t line up. Humbug. His kids seemed to recall him reading them the poem decades earlier. Plus, it just sounded like the kind of thing he would write.

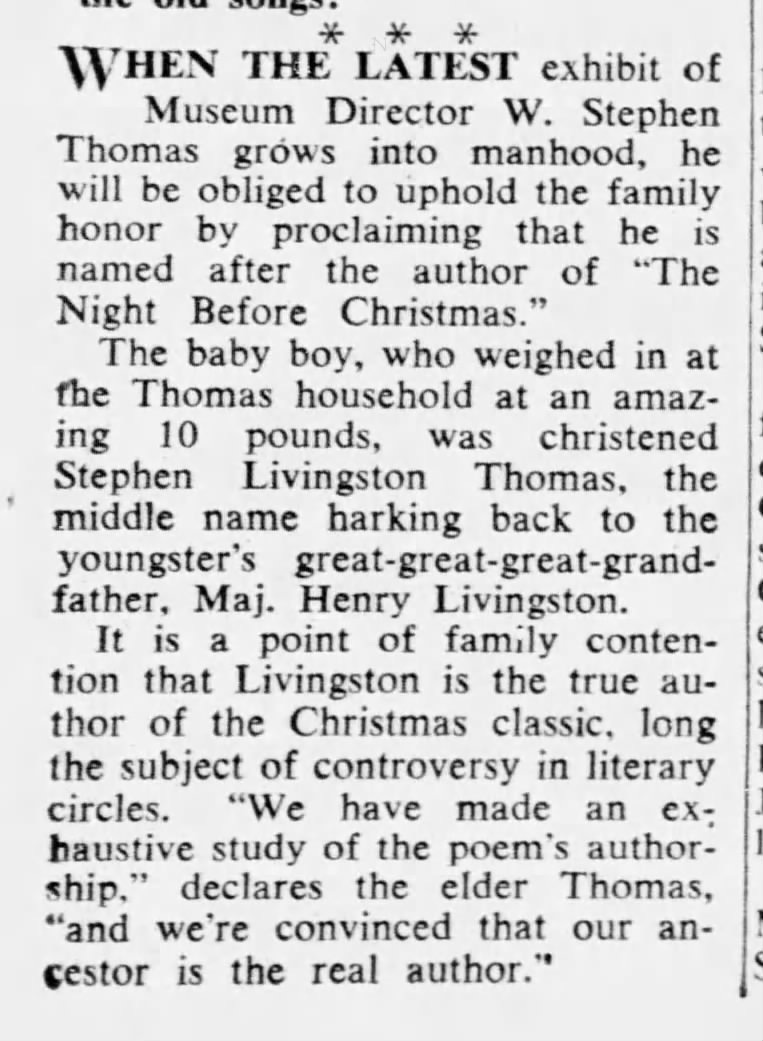

For the next two centuries, members of each generation took up the quest to prove Henry’s authorship as if it were a rite of passage. It got to the point where one of the family’s researcher’s had the following birth announcement issued for his son:

But the claim didn’t really reach escape velocity until a particularly dedicated descendant found a particularly gifted (and perhaps just a little reckless) English professor who styled himself as a sort of literary detective. Their partnership would rewrite Christmas history. Starting in the year 2000, the idea that Livingston wrote the poem became mainstream — even showing up uncritically on the Poetry Foundation website, and in many places besides.

The only problem is - that claim, in my view, is entirely baseless. My story on the battle for the Night Before Christmas is out on Revisionist History now.

It’s funny how some stories never quite settle. This authorship controversy won’t go away — there are even several books on the subject. And there’s seemingly always some bizarre turbidity around this old poem. Show trials on its authorship. Someone editing out Santa’s pipe to send an anti-smoking message, only to get roasted by everyone else on the planet. Or, indeed, theft.

I’d gone to Troy, New York while working on this story, to review some of the original documents, interview the town historian, and hang out with a leading proponent of the Livingston camp (Duncan Crary, a local impresario whose wildly successful Trial Before Christmas declared Livingston the poem’s author and spawned its own Hallmark film). The local library planned to show me an influential 19th century reproduction of a print of the poem depicting Santa Claus. But when I arrived, the library mysteriously had closed early due to “unexpected construction related issues.” I was unable to view the documents.

Earlier today, Duncan sent me a link to this local news story. The print had been stolen from the library the day before I arrived.

Happy Christmas to all. Lock your poems up tight.