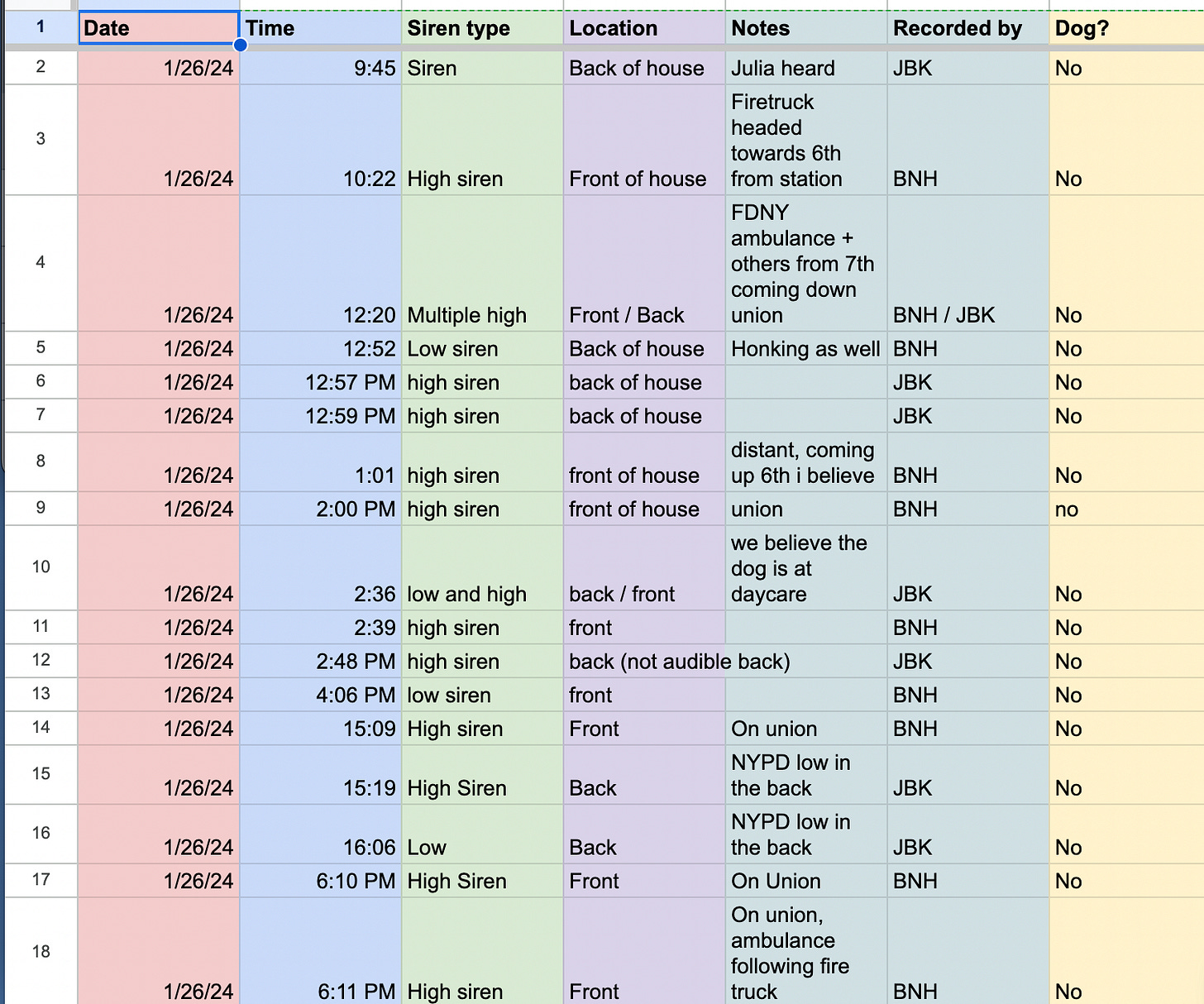

I live across from a fire station in Brooklyn. If something in my apartment caught fire, I’d be golden. But, so far, we’re flame-free.

What we do have, every day, is an ungodly number of sirens.

This is just part of living in New York City. Sirens that, at 120 decibels or so, are capable of permanently damaging your hearing in a single instance, per the CDC; keep you up at all hours of the night; increase noise pollution at levels that can raise the risk of heart disease, hypertension, etc.

But we accept them because of the fact that every 911 call is urgent, and sirens get first responders to the scene faster.

Right? Wrong.

For decades now, a small but growing number of paramedics and EMS medical directors have noticed something strange. A lot of ambulances using sirens were getting in accidents. Also, on average, their sirens didn’t seem to be making that much of a difference in their time-to-caller. The vast majority of calls weren’t urgent at all.

And yet, a lot of firetrucks and ambulances were running hot (meaning, used lights & sirens) to 100% of their calls. So these researchers began to study what the risks and benefits of sirens.

They found out that sirens are dramatically overestimated & overused across the country. And they began a crusade to reform our outdated ideas about sirens.

You can hear more about all this in the episode I wrote and reported for Revisionist History (out today). But, for anyone who’s listened, I wanted to provide an annotated, abbreviated bibliography to give credit where it’s due. I also hope that — should you wish to make the case for a change in your community — these are the resources you need.

It’s all a bit dense. Have I lost the plot? Maybe, sure. But Ahab didn’t catch his whale by being chill. (No one tell me what happens at the end of the book).

Claim 1: Lights & sirens are risky

This is something that’s anecdotally known to be true, but here’s the big, recent study of approximately 19 million 911 calls that showed L&S increase the risk of accident by more than fifty percent en route to a call. It’s even higher transporting to the hospital.

“Is Use of Warning Lights and Sirens Associated With Increased Risk of Ambulance Crashes? A Contemporary Analysis Using National EMS Information System (NEMSIS) Data.” Annals of emergency medicine.

“Emergency Medical Vehicle Collisions and Potential for Preventive Intervention.” Prehospital emergency care.

“Improving Safety in EMS: Reducing the Use of Lights & Sirens” by the National EMS Quality Alliance. [This is a good summary document of research and case studies of communities who’ve made changes to their policies — but not an original study]

Claim 2: Lights & sirens don’t save much time

This is something people have studied for decades now. Helpfully, the leading siren reform researcher, Douglas Kupas (former EMT; emergency medicine physician, Commonwealth EMS Medical Director for the Pennsylvania Department of Health), wrote a white paper for the government in 2017 in which he compiled many of those studies in one place. The range seems to be, on average, 42 seconds to 3 minutes and 48 seconds. Per other studies, it’s an average of 1.5 minutes saved in urban settings; 3.5 in rural.

“Lights and Siren Use by Emergency Medical Services (EMS): Above All Do No Harm” by Douglas Kupas. Prepared for the U. S. Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Office of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in 2017.

“Time savings associated with lights and siren use by ambulances: a scoping review.” International Journal of Emergency Services.

Claim 3: The amount of time lights & sirens save is not essential

… in the vast majority of cases.

The major exception is heart attacks, but overdoses, gunshot wounds, strokes, choking, are all cases where seconds can matter. The thing is, in an analysis of millions of 911 calls to which ambulances responded, paramedics were found to make potentially life-saving interventions (very generously defined) less than 7% of the time. Some of those interventions were likely not even particularly urgent. But they drove with lights & sirens nearly 86% of the time. Other studies suggest that the true L&S response rate could be as high as 97%.

“Using Red Lights and Sirens for Emergency Ambulance Response: How Often Are Potentially Life-Saving Interventions Performed?” Prehospital Emergency Care.

“The Use of Emergency Lights and Sirens by Ambulances and Their Effect on Patient Outcomes and Public Safety: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature.” Prehospital and disaster medicine. [See, in particular, page 212 for a particularly damning summary of research into whether time savings made any difference clinically.]

Claim 4: We can change

Many places have significantly reduced the use of lights & sirens and seen no negative outcomes. You can read some of their case studies here, and listen to the episode for an additional one from Berrien County, Michigan. A couple highlights:

In Berrien County, Michigan, Jonathan Beyer halved the use of lights & sirens and it made no difference to patient outcomes.

In Fort Worth, Texas, and 14 surrounding cities (an area of over a million people), Jeff Jarvis reduced lights & sirens by about a third. Response times increased by a median of 6 seconds.

Douglas Kupas, in Danville, Pennsylvania, has reduced the use of lights and sirens usage to 8% when responding to calls. 1% returning from them. Their cardiac arrest survival rate is about 50% higher than the state average.

Claim 5: This logic applies to the majority of sirens you hear

Per FEMA, police cars use their sirens less often than ambulances or firetrucks. So most sirens you hear are probably ambulances and firetrucks, depending on where you are. But firetrucks don’t actually respond to fires much anymore, on a national basis — fewer than 4% of their calls are for fires. That’s less than the number of false alarms they respond to. The vast majority of their calls? EMS and rescue.

Claim 6: Sirens are a vestige

If you’ve made it this far you probably live in my apartment with me. And I thank you. But this is my last point. Sirens on firetrucks and ambulances are an artifact of the fire system as it was when EMS was first established nationwide in the 1970s. Fires spread. They are almost always situations where seconds count. So firetrucks, historically, used their sirens all the time. And fire stations housed the early paramedic programs. So ambulances operated according to fire culture rules. Those rules apply in neither case now. This is something a few people in the field told me, but it came up here too:

“The Maximal Response Disease” by Jeff Clawson. Medical Priority Dispatch.

“EMERGENCY!: Send a TV Show to Rescue Paramedic Services” by Paul Bergman. University of Baltimore Law Review [somewhat unrelated, but it was helpful in my piece]

“Transporting Lazarus: Physicians, the State, and the Creation of the Modern Paramedic and Ambulance, 1955–73” by Andrew T. Simpson. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences.

You may not be bothered by this like I am. But I think the case against sirens goes far beyond noise. And it’s a good reminder that some things we take for granted are really just vestiges of another world. It’s not a bad thing to want fast emergency service. But if you were designing the system today, the ubiquitous siren — ruining our hearing; risking the lives of pedestrians and first responders for minimal benefit — is the last thing you’d think of. The burden of proof has shifted.

If you, like me, can’t get enough of this topic, you can listen to the episode or write me. Thank you for reading!

I really enjoyed this episode - I'm a local elected official who liaises with emergency services, so much of this hit home for me. For example, in support of your thesis, I listen to scanner traffic and am shocked at how many EMS calls are to transport someone from a nursing home to a hospital because of lab tests that came back out of spec, or someone fell and needs help up. And I appreciate the point about computer aided dispatch and determinant codes to decide on response priority.

But... many calls come in as a medical alarm, no details. How should we respond to that? When you don't know if it is a heart attack or a fall? What about smoke alarms that go off? Shouldn't the fire department respond to every alarm drop as if it is a structure fire that needs rapid intervention? Or police! They get so many 911 open lines or 911 hang-ups, which could either be a kid playing with a phone... or a serious situation that requires immediate intervention.

Lastly, and I don't have details on this but maybe could be an interesting follow-up, is around the sirens. Why are US sirens different than Europe? Is one better than the other? Also, I've heard of a new type of siren called the "rumbler" that is supposed to be more effective than the Federal Q.

Thank you for this episode and for the resources, I dug it up again today after a sleepless night of sirens waking my preschooler and making my dog howl. In PA, a lot of our fire depts are volunteers, making the argument that they "need" the whistle/siren to alert them to a callout, despite pagers and cellphones being far more effective and less harmful alternative. Did you encounter anything with respect to volunteer operations in your research? Do you think the most tactful approach is to the dept. themselves or local officials - or some combination of the two?