On the day after New Year’s, 1968, Bob Citron turned the key to his new offices at 60 Garden Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was greeted with word that two volcanoes — erupting several thousand miles apart — had created brand new islands in Antarctica’s Telefon Bay and in the South Pacific near Tonga. Eyewitnesses saw the latter burning red, spouting a column of smoke thousands of feet into the air.

The telex began to clack, the phone began to ring, the lava set, and the Center for Short-Lived Phenomena came roaring to life.

I first learned of the Center a couple years ago when, reading through a correspondence file in the New York State archives, I noticed its bizarre letterhead. Its name alone was enough to intrigue me. It was a Smithsonian organization, so I wrote Smithsonian magazine and suggested they send me into the archives to piece together the organization’s history.

That essay is out in this month’s issue of the magazine, and online here. I’m including some of my favorite material that didn’t make the cut below.

The Center was meant to solve a very big problem: Interesting, unusual things are happening all over the world, all the time. But usually, scientists didn’t find out quickly enough to study them as they occurred. The Tonga volcanic island, for instance, only existed for 58 days, at which point it sank back into the ocean.

Getting people there in time took vigilance and vision. It found both in Bob Citron.

The mustachio-ed 37-year-old director of the Center had found his dream job. He was a Zelig-like figure in Cold War science — the guy who first recorded the sound of Sputnik as it passed over California (if you’ve ever watched news footage about Sputnik from that era, you’re likely hearing his recording). Eisenhower sent him a telegram. Later, he became an early and important figure in private space flight. He described himself as “an expert in nothing, but I deal with experts in everything.” His trip itineraries were exhausting; his interests exhaustive; his license plate read ‘STARMAN.' He was thrice married, each time to the love of his life. Short was the correct length for a phenomenon.

The archives of the Center are a record of his quicksilver obsessions and his fanatical dedication to global science. He had a small staff, and to keep the network together, he was in near constant contact with scientists around the world about an extremely varied set of topics. “All we ask,” he wrote to a scientist in Yugoslavia, “is that you notify us of short-lived natural, unpredictable events that occur in your area or that come to your attention from nearby areas.”

Much of what came back was on the scientific fringes. “Here, in Mauritius, we have a strange phenomena,” one far-flung correspondent wrote. “A doll which speaks weeps sings and answers to questions [but is] an ordinary doll … it belongs to an Indian girl whose parents and herself are very anxious.”

“We welcome you as a correspondent of the Center,” the Center responded. “The doll which you mention in your letter suggests ventriloquism but I have no idea what it is, not having seen the doll.”

In the span of nine months, the CSLP expanded the reporting network to 384 correspondents in 71 countries. By 1970, it had grown to 2,400 scientists in 134 countries. It became an invaluable source of reports, not so much about haunted dolls, but about volcanoes, oil spills, and everything in between. Over time, the Center’s audience came to include high schoolers, journalists, scientists and administrators across the US Government, and higher-ups at NASA.

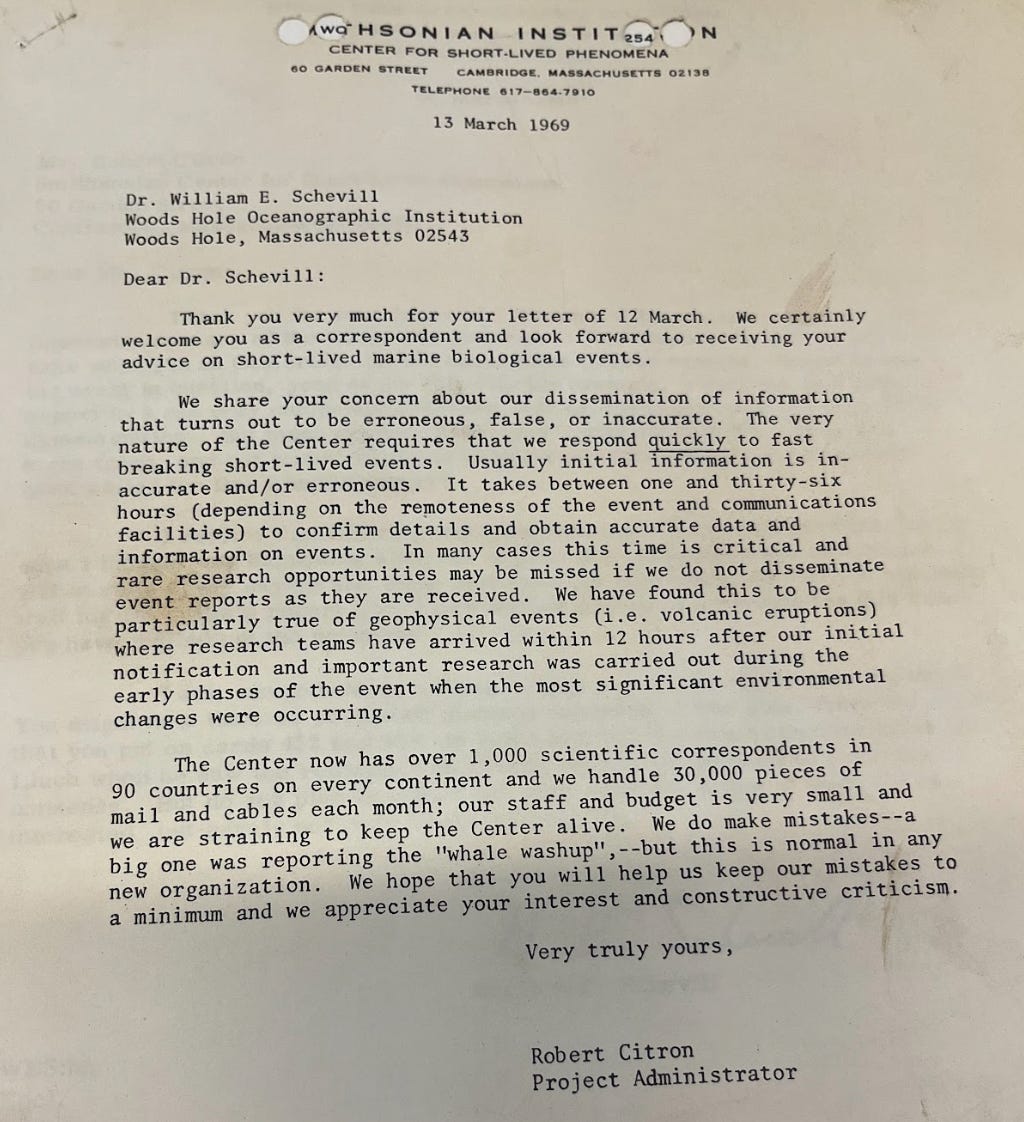

It was, nevertheless, sort of a shoe-string operation. The best way to picture the CSLP is to imagine if Wes Anderson made a movie about scientists in the 1970s. Whimsy and hijinx abound — of particular note, the several letters of damage control peppered in the archives from right around the time the Center announced that a pre-historic sea monster (complete with horn) had been found in Mexico. It was a beached whale.

“The ‘horn’ was a piece of bone which had somehow got pushed through its skull,” Citron said, maybe a little too regretfully.

CSLP’s publications had multiple audiences, including a press corps who found it charming. Dubbed the ‘disaster squad,’ they were written up in papers across the country; Citron chatted warmly with Dick Cavett on network TV; the Center was profiled on NPR. “I receive communications almost every day from an institution called the Center for Short-Lived Phenomena,” Renata Adler wrote in her semi-autobiographical novel Speedboat. “I have received postcards about the progress of the Dormouse Invasion of Formentera…The Samar Spontaneous Oil Burn. The Hawaiian Monk Seal Disappearance. And also, the Naini Tal Sudden Sky Brightening.”

In Adler’s haunted, disjointed book about a haunted, disjointed peeriod in American history, the Center’s oddly upbeat, semi-apocalyptic cataloging fit perfectly.

In the end, the Center couldn’t last. It was often in budget crisis, plus, as soon as the predecessor to the Internet emerged in 1969, it became clear that having Bob frantically call every scientist he could think of anytime something interested happened anywhere wasn’t super practical.

I love the history of the Center, though. It’s a clear illustration of just how hard it used to be for scientists to share knowledge. So much of our knowledge infrastructure was built, in part, to solve that problem — from physical universities, to scientific journals, and ARPANET, the precursor to the Internet. In a closed, Cold War world, it had a particular impact.

Now, we have the opposite problem: There’s so much published research available online, at our fingertips, there’s just no way for any person to stay across it all. One idea is AI will synthesize it for us, network and a correspondent all in one.

It’s an appealingly futuristic dream. But you don’t get there without the brief reign of the Center for Short-Lived Phenomena.

Housekeeping

Hitler’s Olympics, The series Malcolm Gladwell and I wrote this past summer, has just been nominated for a Webby in the ‘Best Writing’ category! You can listen to it here; and vote for it here.