I still remember reading one of my favorite academic essays for the first time. I was researching James Tiptree Jr., the science-fiction writer, who was actually Alice Sheldon, writing under a pseudonym. Sheldon had other pseudonyms too. Including: Raccoona Sheldon. She loved animals. She’d done graduate work in animal psychology, using the standard lab rat. She also wrote a short story called ‘The Psychologist Who Wouldn’t Do Awful Things to Rats,’ which I loved.

I wondered what her principled defense of the lab rat had to do with the animal in her name — ‘Raccoona’ — and somehow that question led me to “The Problem of Raccoon Intelligence in Behaviourist America” by Michael Pettit.

A brief rat detour (then the raccoons)

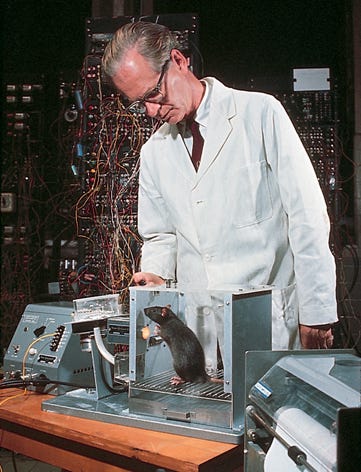

Sheldon got her PhD in the heady era of rat studies, where all sorts of conclusions about human beings were premised on what could be said about rat behavior. The dominant psychological framework of the early-mid 20th century was behaviorism, which sought to make psychology a more reputable science by excising the mind and sticking with the hard, observable data of behavior. Often, animal behavior.

Lab rats were its lingua franca, with pigeons a close second.

The Norway rat is thought to be the first animal that was domesticated for scientific research. The scientist John Calhoun wrote the defining book on the rat, and it was called The Ecology and Sociology of the Norway Rat. As the authors of Rat City: Overcrowding and Urban Derangement in the Rodent Universes of John B. Calhoun point out: “sociology was exclusively the study of human social relationships … he’s proposing an equivalence between the social behavior of rats and that of humans.”

This kind of slippage — rats to humans to rats to humans — paid off big-time for 20th century science. There were rat studies for all kinds of human questions: depression, rationality, empathy. When you say you’re “stressed out,” you’re citing the rat studies of Dr. János Selye, which defined stress.

We still do this with our language: Lab rat, gym rat, smell a rat, rat in a maze, the rat race, etc. It’s all rats, all the way down.

But it turns out that the choice to use lab rats as the defining model organism of the 20th century was largely a matter of convenience. There was a lab rat industrial complex, which helped lead us to some flawed conclusions about human beings.

But there was once a very promising alternative model organism.

The lab raccoon.

The problem of raccoon intelligence

In his article, Michael Pettit details the pioneering raccoon research of Lawrence Cole, an Oklahoma-based psychologist who happened into a colony of raccoons and decided to investigate exactly how intelligent they were.

Cole had gotten his raccoons as pups. This would be before they become, in the words of a raccoon expert I spoke to, “bitey.” It would be hard not to love them. He wrote,

“I may say that I do not believe that my raccoons can fairly be called ‘victims’ of experimental conditions. As long as they continued to suckle…they were fed from a bottle twice each day until fully satisfied. During August, bits of apple, lumps of sugar and water were added to their bill of fare…The animals have been kept in a room 14 by 10 feet, in which they could climb about on several roles of poultry wire which were hung on the walls. They had there a nest of hay. Two windows, in which they frequently sat, were open in the summer. They could climb about and they were frequently let out to follow me over an open field, climb nearby trees, or play about the house.”

This was a far cry from the decades of starving, organ harvesting, and zapping awaiting the lab rat. Cole tried to launder his raccoon love through scientific language — assigning them numbers in his study — but in reality, he called them Jack, Jim, Tom, and Dolly.

His experiments, and the experiments of another scientist working at the same time, suggested that raccoons were really intelligent. Maybe as smart as monkeys or small children. And Cole thought they could hold images in their minds. Which was an explosive thing to claim of any animal at the dawn of behaviorism.

For the behaviorists, this was all very inconvenient. Raccoons were hard to corral for studies. People focused on getting tenure couldn’t really be bothered with recapturing a colony of experimental raccoons who have broken out of their cages and moved into the lab’s ductwork (true story). Lab rats stay in cages. They don’t need lumps of apple and bits of sugar. They eat whatever. Easy.

So the raccoon model was quibbled with, shot down, and then forgotten.

I made an episode of Revisionist History this week interviewing Pettit and some animal scientists to try to understand: What was the consequence of this raccoon erasure? What would have happened if we’d picked them, rather than rats, to be our model organism?

It’s a bit of a lark, and I have more to say on this (including an upcoming newsletter on pigeons). But I hope you enjoy it.

Meanwhile in mammalian intelligence…

My friend and colleague Lucie Sullivan made a great episode about prosopagnosia — or face blindness. Convenient excuse or medical condition? You decide.

Bird brains vs. your brains, courtesy Nathaniel Naddaff-Hafrey.