Player Piano

A mid-century composer's obsessive quest to create a songwriting machine, and the perils of artificial intelligence.

The Last Archive returns

Thank you for signing up for this newsletter! We just launched season 4 of The Last Archive, and I’m planning to use this newsletter to share some archival material & stuff I loved but had to cut from each week’s episode. Later, it may become a more general place for updates. Feel free to forward this to other people too. It will never be too frequent — scout’s honor. Onto episode one…

Episode 1: Player Piano

Raymond Scott was one of the most famous musicians of the 20th century, but he died nearly forgotten in the 1990s.

When researchers dug through his papers, they discovered something unknown in his lifetime: He’d been hired at Motown in the 1970s to build a machine that was meant to help write songs.

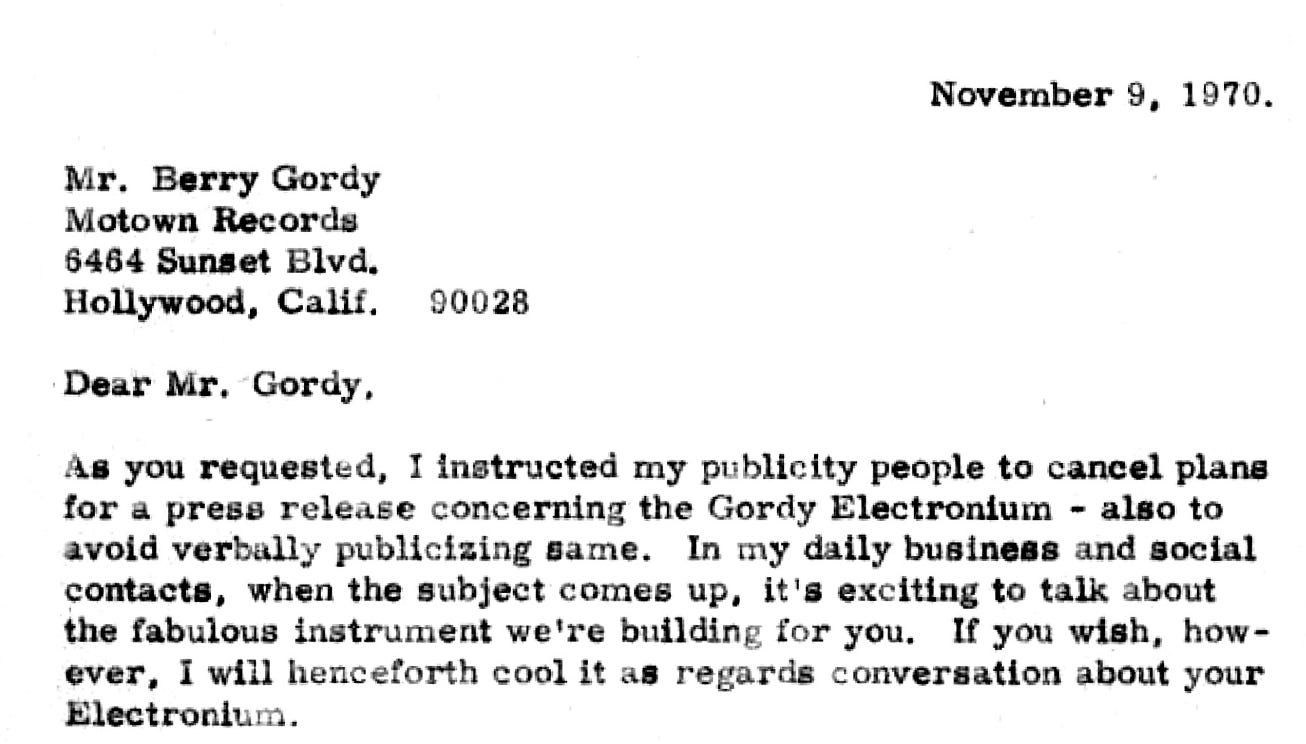

Scott dedicated much of the rest of his life to the machine. He worked in secret - Berry Gordy Jr., president of Motown, reprimanded him for publicizing the agreement, leading to my favorite response: “I will henceforth cool it.”

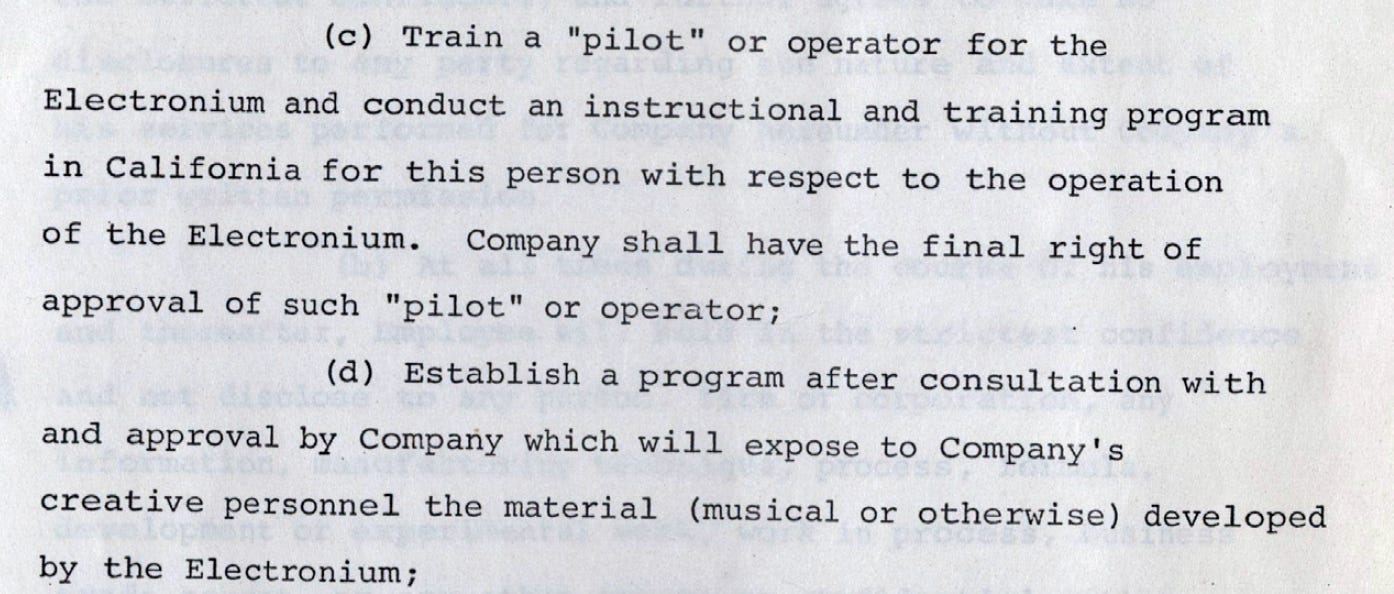

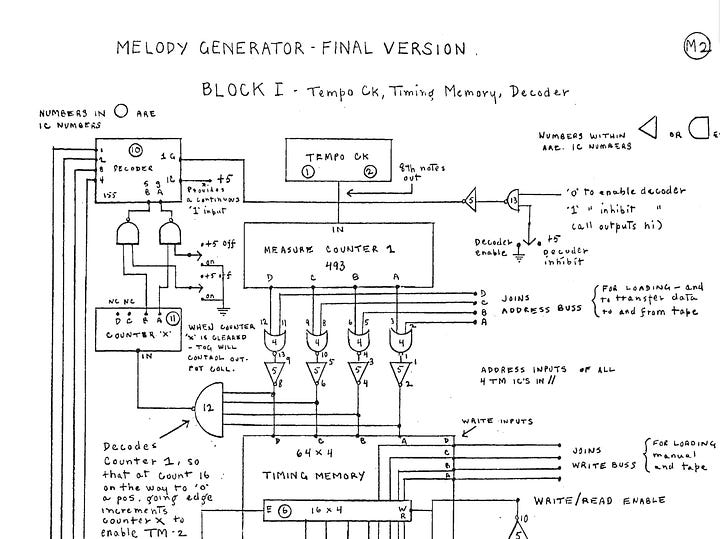

Scott’s idea was that the Electronium could be a partner to a human composer (whom he called a ‘pilot’ or ‘guidance control’). Notably, the machine did not have a keyboard. It looked like the cockpit of an airplane. Its primary functions were:

You could program in a song as if it were a player piano (witness: the disastrous ‘Cindy Electronium’).

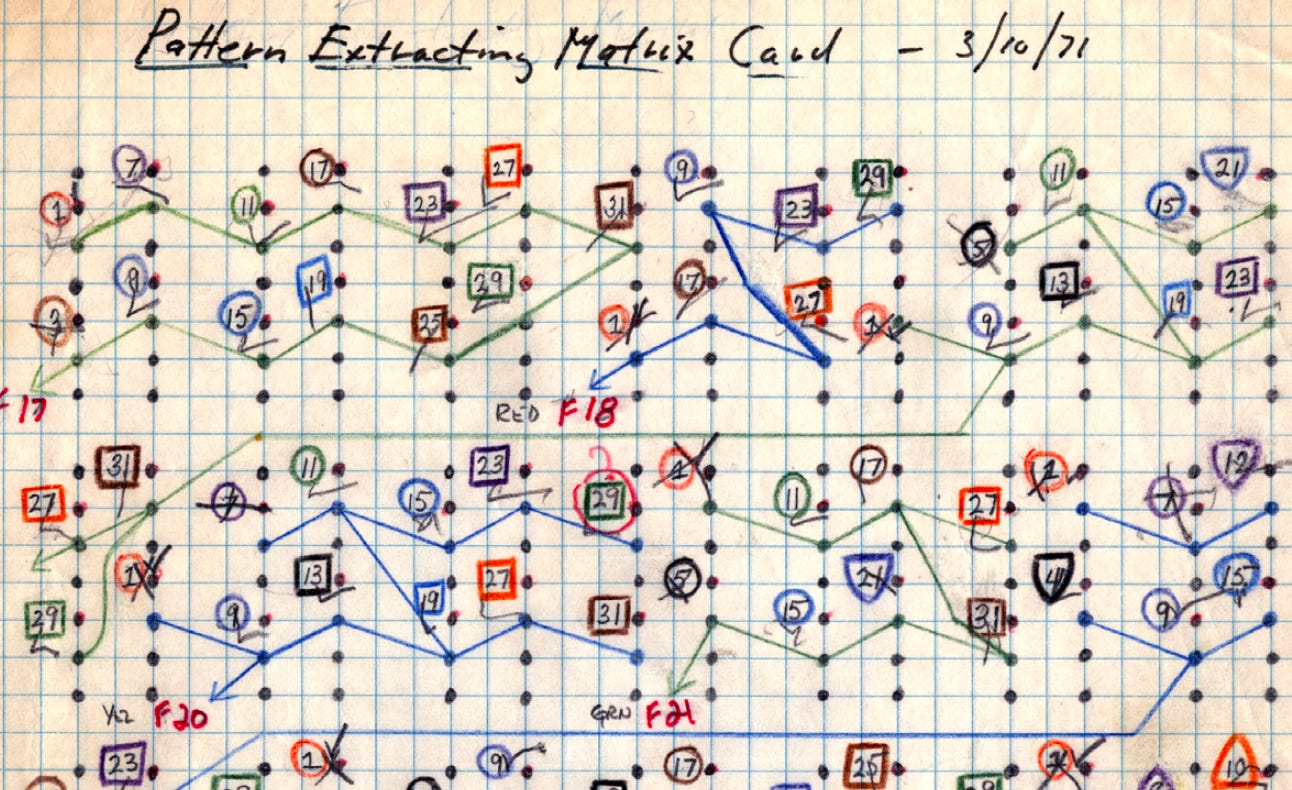

You could use the machine to automatically arrange or change a preset pattern (widen the intervals, quicken the tempo, add counterpoint).

And, most significantly, you could have the machine ‘iterate’ semi-randomly on an idea, waiting to see if it hit on a hook that sparked for a user.

Tom Rhea, who taught electronic music history at Berklee College of Music, told me, “I’ve always considered Raymond Scott one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence in music.”

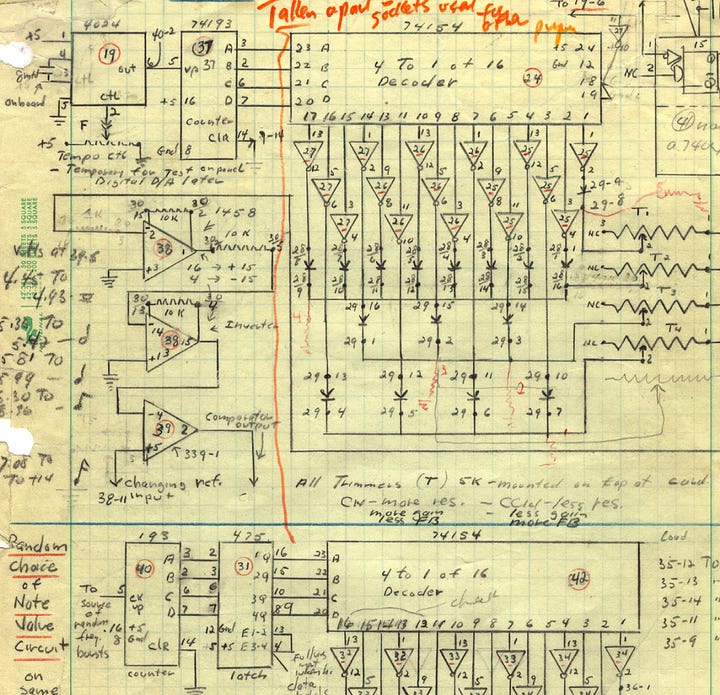

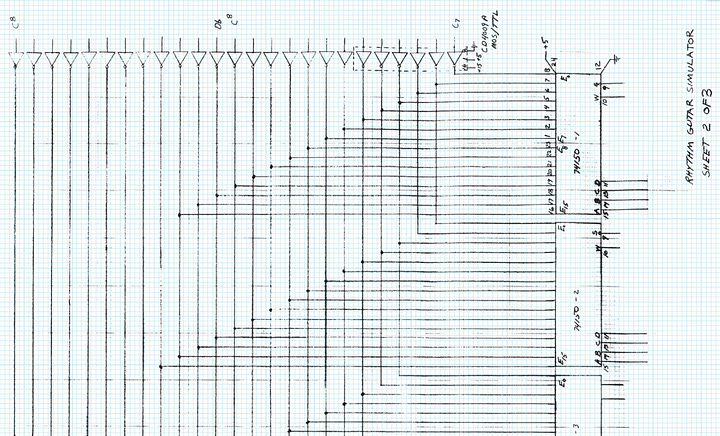

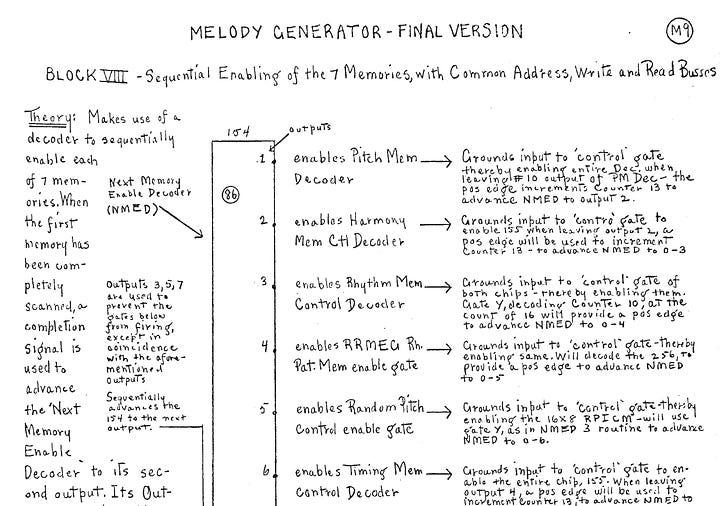

Scott began building the machine in 1959, within a year of the first artificial neural network (Frank Rosenblatt’s Perceptron). There were no computers involved — just a byzantine electromechanical system.

Scott worked on the machine above Gordy’s garage, and eventually in a small room on the second floor of Motown. One engineer remembered Michael Jackson watching the machine work. Scott’s employment agreements & notes from his conversations with Gordy suggest they saw it as an idea generator — akin to the way people are using ChatGPT to brainstorm now.

There were even suggestions of hiring someone to run the machine and edit the best ideas to give to Gordy. These are notes of a conversation between a Motown engineer, Scott, and Gordy, but it’s not clear who among the three proposed this. Gordy hasn’t responded to my requests for an interview; nor, I believe, has he spoken to the Scott archivists.

Berry Gordy Jr. founded Motown in 1959 in Detroit, the same year Scott began work on the Electronium. Before founding the company, Gordy had worked at a car factory, during the years when there was lots of hubbub over plants that had achieved near-full automation. It was on the assembly line that Gordy started to think about doing music differently. In his autobiography, he wrote, “At the plant, the cars started out as just a frame, pulled along on conveyor belts until they emerged at the end of the line… I wanted the same concept for my company, only with artists and songs and records.”

This, then, is an early window into efforts to automate the creative process for commercial purposes. The questions raised by GoogleLM or Deepfake Drake are the same questions posed by the Motown Electronium. Raymond Scott’s life is key to understanding not only how much deeper this history runs than we typically assume; but also to measuring the risks of excessive faith in what can be automated.

Scott taught himself to play piano from the player piano — itself an automatic performance machine. He ended his life trying to create a machine that could replace the composer as well. Along the way, he alienated many people through his will to control, and an obsessive perfectionism. This episode tells that story — a man at risk of forgetting the humanity of the people around him, and ultimately his own.

The Electronium is sitting in storage on the west coast. A team of people are hoping now to bring it back online. But until they do … you could pass the time with a podcast?

All scans courtesy of Raymond Scott Archives. Thanks to the Marr Sound Archives for all the Scott archival tape in the episode. Listen to the episode here!