Some months ago, I learned that a partner at a large law firm was talking to his clients about English Muffins.

Specifically, the secret recipe for Thomas’s English Muffins, and the man who, allegedly, tried to steal it.

I was intrigued.

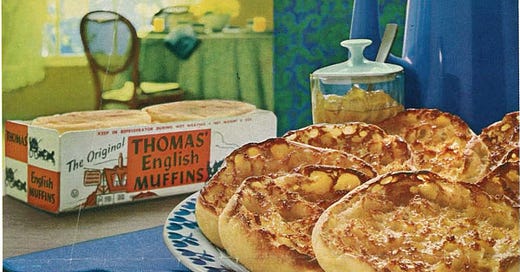

In 1874, an Englishman named Samuel Bath Thomas came to the United States. He had in his pocket a recipe for what would’ve been called crumpets or Welsh muffins — overproofed (over-fermented), then baked on a griddle, so they’re crisped on the outside and pocked on the inside, the better to catch butter with.

More than a century before the Cronut made landfall, Thomas’s English Muffin took New York by storm. By 1880, he had his own bakery. Soon, he was delivering by horse and wagon all across the city. When he died, his family started a corporation to make the muffins in perpetuity. There was just one problem.

An English muffin is not very hard to make. There is, in today’s jargon, essentially no competitive moat. So they had to keep their recipe a secret. From 1874. Until 2010.

That’s the year of the alleged English Muffin theft. In 2009, Grupo Bimbo, a gigantic Mexican baking conglomerate, purchased Thomas’s English Muffins and its trademark nooks and crannies (literally - look at other english muffin packages, it is verboten to say ‘nooks and crannies’ unless you are Thomas’s. This is why Dave’s Killer English Muffins have ‘butter-catching flavor craters’).

Samuel Bath’s muffins were, at this point, bringing in about half a billion dollars a year in revenue. For something made mainly out of water, that’s pretty good.

But now it was even more difficult to compete with all the other English muffin makers. So, the muffin was a military-grade secret.

According to Bimbo, only seven people at the company knew all the information required to make a Thomas’s English Muffin. The recipes were kept in code books accessible only to those who needed them.

One of those people was Chris Botticella.

Botticella was a middle-aged Bimbo executive, who oversaw West Coast production for Bimbo Bakeries USA, including the Placentia, California, facility where the English Muffins were made. But lately, he had been unhappy. There’d been cost-cutting and layoffs. For a man who had been born in a baking family, and been in the business since he was 16, seeing bakers lose their jobs was tough. So, when Hostess (famed Twinkies purveyor) came knocking, he took a job with them.

Except he didn’t leave Bimbo right away. To hear him tell it, he was waiting for a year-end bonus. He remained in his job for months, privy to confidential information, until Hostess put out a press release announcing his hire. At which point Bimbo fired Chris immediately. And then sued him to stop him from taking the Hostess job, telling the judge that he was one of the few people who knew the muffin secret.

Things went awry from there. You can hear the story of the case in a two-part episode of Revisionist History, in which I work with the CIA (the Culinary Institute of America - what did you think I meant?) to reverse engineer the secret muffin.

Should this really have been two parts, some have asked, and I can only tell you that we had fun, and there’s only so much you can cut from a Willy Wonka digression before it just loses the joy.

Besides, there are intellectual stakes, if you’ll only read on…

I was interested in the story because of all the layers of myth around … a muffin. Whenever people make a religion or a cult out of a product or business — what the scholar Eugene McCarraher calls “the enchantment of capitalism” in his excellent The Enchantments of Mammon — something funny is going on. And in this case, there were serious legal implications. For Chris Botticella, at least.

I wound up in the end feeling like this muffin secret was a bit of marketing, and a convenient legal technology for controlling employees who, it must be said, were not behaving entirely straightforwardly. But as I talked to legal experts who teach the case about the rising utility of trade secrets in a post-non-compete world, I began to worry about a future of mounting corporate mysticism and secrecy, with troubling implications for us all.

Anyways, if you listen here or here, I hope you enjoy.

P.s. 3/4 of the way through the second episode, I speak to the first American Carthusian monk (now a sensei, go figure) and one of the only people in the world who knows the full recipe for Chartreuse. I may revisit that in a later newsletter - it was a pretty incredible conversation. Shout out to Becky Cooper for putting me onto the story of Chartreuse!

So good

great stuff